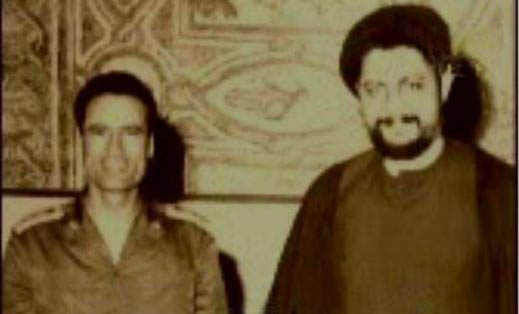

The Imam and the Colonel.. Filmmaker: Abdallah El-Binni - Al Jazeera World

Could the end of Muammar Gaddafi's

rule help solve the mystery surrounding the fate of a missing Lebanese imam?

Al Jazeera World - 24 Jul 2012 13:40

Filmmaker: Abdallah El-Binni

The downfall of Libyan leader

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi last year was greeted with great hopes for the rebirth

of a nation.

But there was another hope felt by

many inside and outside of the country - that the end of his 42-year rule would

allow some light to be shed on the fate of a charismatic Lebanese cleric.

Imam Musa al-Sadr, the leader of

Lebanon's Shia Muslims, disappeared, along with two companions, in the summer

of 1978 during a visit to Libya to meet Gaddafi.

Hand-painted portraits of Imam Musa

al-Sadr can still be seen on the streets of Lebanon, 34 years after he

disappeared

As in the Shia myth of the 'hidden

imam', this modern-day cleric left his followers upholding his legacy and

awaiting his return.

The enigmatic cleric's popularity

had transcended religions. Calling for social justice and development, in 1974

al-Sadr founded the Movement of the Deprived - aiming to unite people across

communal lines.

Archbishop Youssef Mounes of

Lebanon's Catholic Information Centre remembers a sermon al-Sadr delivered in a

church, in which he warned of an imminent sectarian war.

"It was a surreal scene,"

Mounes says. "Seeing the turban of a Muslim imam under the cross in a

Christian church. He delivered a sermon at a very significant time."

Raed Sharaf al-Din, al-Sadr's

nephew, recalls how his uncle believed that Lebanon's sectarian nature could

cut both ways: "Imam al-Sadr used to say that sects are a blessing, but

sectarianism is a curse. It's a blessing to have this diversity of sects in

Lebanon. But when there is strife among them, sectarianism is the worst thing

for a country."

When civil war erupted in Lebanon in

1975, al-Sadr led anti-war protests. And as the war intensified, so too did

al-Sadr's efforts to end it. As part of this, he toured the Arab world to plead

the case for south Lebanon.

In 1978, this took him to Libya

where he was due to meet Gaddafi.

He was never seen again.

In the years since, conflicting

stories have emerged about what happened to al-Sadr and his two companions. Now

hopes have been raised that new evidence and witnesses will emerge to help

solve the mystery of the missing imam.

Discovering the vanished imam

By Giles Trendle

In January 1990, I travelled to

south Lebanon to report on the ongoing fighting between Lebanon's two main Shia

Muslim militias, Amal and Hezbollah.

The road to south Lebanon led

through the notorious Ouzai district of Beirut, skirting the city's southern

suburbs where Hezbollah held sway and where a number of Western hostages were

believed to be being held captive.

Large, hand-painted portraits of two

clerics hung from rusting electricity poles all along the stretch of road.

One showed the brooding scowl of

then Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The other portrait was of a

man with an altogether different demeanour - softer, more enigmatic.

The picture captivated me. I knew

this to be Imam Musa al-Sadr, but I knew little about the man.

By the time I drove past the two

portraits of the Shia clerics, al-Sadr had been missing for 12 years.

The charismatic imam became the

leader of Lebanon's Shia Muslim community, but his popularity transcended

religions

His portrait had captivated me then.

How much more so did he enthrall his own people, and many others in Lebanon,

when he was alive.

Musa al-Sadr was born in Iran in

1928 to a prominent Lebanese family. He moved to Lebanon in 1959 after

undertaking religious studies in the eminent seminary of Najaf in Iraq.

Al-Sadr found the Shia in Lebanon

resigned to poverty and political exclusion. They were lorded over by feudal

masters from within their own community and by the more urbane political

classes from Lebanon's other sects.

The 1943 Lebanese National Pact had

largely kept the Shia on the political sidelines. The unwritten agreement

granted them the 'speaker' of the parliament, a third-place position behind the

more powerful Sunni Muslim prime minister and the Maronite Christian president.

Al-Sadr clearly had a way of

attracting attention and inspiring people. Six-foot tall, striking and

charismatic, he spoke of reform, greater justice and empowerment for the

masses. Within 10 years he was appointed as the first head of the Higher Islamic

Shia Council - effectively becoming the leader of Lebanon's Shia community.

When civil war erupted in Lebanon in

1975, al-Sadr held sit-ins and fasts to protest against the violence. He

campaigned for inter-communal harmony and tolerance.

One famous story has him being

invited to speak in a church. The Christian worshippers packed the aisles of

the church to hear the cleric deliver a sermon on the blessing of diversity and

the dangers of sectarianism.

A turbaned Muslim cleric speaking

beneath the Christian cross - this was the self-assured and ground-breaking act

of an innovator, someone ready to cross the sectarian fault lines in a country

with deep and primordial confessional tendencies.

Many lauded the cleric for his stand

against violence and prejudice. In his book The Vanished Imam, writer Fouad

Ajami drew comparisons to Mahatma Gandhi. Others have made comparisons to

Martin Luther King.

But al-Sadr was a man of many

dimensions, in a region of countless nuances. Caught up in an environment of

endemic violence, he understood the necessity for self-defence and he

established a militia called Amal.

So who would have wanted him dead?

In the film, some well-placed

Libyans say al-Sadr was killed after an acrimonious quarrel with Gaddafi on a

point of religion. The cleric's own family members hint at a darker

international conspiracy.

The context at the time of al-Sadr's

disappearance is revealing. In the summer of 1978, Iran was heading towards a

climax. Al-Sadr was in cahoots with opponents of the pro-American (and

pro-Israeli) Shah of Iran.

As it was, the Shah fled his country

in January 1979 and the Iranian revolution culminated a few weeks later with

the return of Ayatollah Khomeini from exile. Al-Sadr had disappeared five

months earlier.

The revolution in Iran amounted to a

Shia awakening. And with this backdrop, supporters saw in the case of the

missing cleric a more potent symbolism dovetailing neatly with the Shia belief

in the disappearance of the 12th imam in the 10th century.

The awakening found devotees in

Lebanon. Backed by the new Shia theocracy in Iran, and forged from the fury of

Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, a new movement of Shia militants emerged,

calling themselves Hezbollah. A year later they came to world attention when

suicide bombers struck the US embassy in Beirut and then the barracks of the US

and French 'peacekeeping' forces in the Lebanese capital.

Giles Trendle with an Amal fighter

in Kfar Hitti in 1990

Two years later, in 1985, I arrived

in Lebanon for the first time.

The country had by then become a

synonym for anarchy and carnage. Moving around those parts of Beirut controlled

by Hezbollah was inadvisable for a Westerner such as myself.

But five years on, I was heading to

south Lebanon, through Hezbollah neighbourhoods, past the portraits of the

clerics on the road through Ouzai and on to the village of Kfar Hitti, some

15km inland from the coastal town of Sidon.

Inter-Shia fighting had been raging

in the area. In Kfar Hitti, Amal militiamen stood behind sandbagged positions

looking across the rocky terrain towards the neighbouring village of Kfar Melki

where Hezbollah fighters were emplaced.

The Shia had turned their guns

against themselves. Hardly the sort of legacy al-Sadr would have wished.

Today, more than 20 years on, Amal

and Hezbollah have buried the hatchet. They are now more politically aligned.

Both groups have allied themselves closely to Bashar al-Assad's Syria.

Something of an irony: the heirs of al-Sadr, himself a victim of one

long-serving Arab autocrat, rallying to the side of another.

Back in the 1970s, al-Sadr spoke of

the dangers of sectarianism. He had sought ways to reach across religious

divides.

With the dark clouds of increasing

sectarian violence on the horizon in Syria, and possibly Lebanon, those with

such a message of inter-communal compassion will be sorely needed in the

region.

The views expressed in this article

are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial

policy.

Comments

Post a Comment